Rice is a regular must-have at the dining table for Malaysian families from all walks of life. Prof Anna Ling, Dean at the IMU University’s School of Health Sciences, talks about how rice research will help to ensure that the supply of this staple grain remains stable and sustainable in our country.

Rice is as much a staple food for Malaysians as it is an integral part of our identity. Imagine your nasi lemak without the nasi, banana leaf rice without rice or your chicken porridge made from oats. Traditional Malaysian cuisine would be at a loss without this unassuming but essential grain. Yet a lot of the rice that we eat is not homegrown. We still rely heavily on imported grain to meet our country’s needs – and wants – with an estimated 1.1 million metric tonnes of rice brought in annually.

“High dependence on rice imports is making Malaysia more vulnerable to the risk of food price inflation,” says Prof Anna Ling, Dean of the School of Health Sciences at the IMU University. She explains that any disruption in the rice supply chain, such as a poor harvest, climate change or geopolitical tensions among the rice-importing countries, will have a significant impact on rice availability and affordability for the country.

These scenarios are not just rhetorical. Take for example the current, record-setting heat wave in Southeast Asia which has brought global climate change right into our everyday lives. While we are able to turn up the power on our air conditioners to regulate the temperatures of our living rooms, offices and bedrooms, agriculture is not as lucky. The unpredictable weather brought on by climate change cannot be regulated in wide open fields, and this has significantly impacted our food sources such as rice.

According to the data from the Ministry of Agriculture, during the period of 2017 to 2021, a total of 9,336.45 hectares of paddy fields were lost due to drought, while 40,828.28 hectares were destroyed due to flooding in Malaysia. This has consequently led to a decrease in the nation’s self-sufficiency ratio (SSR). In 2021, Malaysia’s SSR for rice was recorded at 65 per cent and it dropped to 62.6 per cent in 2022.

A Robust Rice

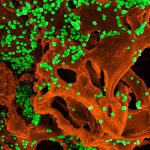

While there is a concerted world effort to curb the global warming crisis, scientists such as Prof Anna are taking up the challenge on the other end – developing climate-resistant crops that can tolerate extreme temperatures, drought, flooding and other climate-related stresses.

Since 2009, Prof Anna and her research team have been collaborating with the Malaysian Nuclear Agency, public universities, research institutes and other international agencies such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Forum for Nuclear Cooperation in Asia (FNCA). The collaboration has been led by Japan and has utilised advances in biotechnology, such as mutation breeding, genetic engineering and gene editing, to find opportunities to enhance the traits of new rice strains.

The collaboration has produced several advanced rice lines, some of which have gone through extensive screenings in laboratories and fields. “We have successfully produced new rice varieties that are resistant to unpredictable climate change such as drought and flooding. One of varieties, NMR152 was officially released and launched by the honourable Prime Minister of Malaysia in November 2021” says Prof Anna.

These new rice varieties also possess enhanced traits such as better resistance to disease and early maturity, which helps to reduce the burden on farmers and the environment. For instance, early maturity reduces the usage of fertilisers, while disease resistance reduces the usage of pesticides to a minimum level. The benefits to the environment are obvious, and “from an economic viewpoint, this is crucial to the farmers as the price of pesticides has increased by over 100 per cent in the last 10 years,” says Prof Anna.

Advances in the Field

The hunt for new rice varieties is not new. Similar research efforts have been conducted previously using methods such as mutation breeding, which remains widely accepted and reliable for producing new rice varieties. However, current breeding techniques utilise more advanced technology. “For instance, we employ ion beam radiation technology instead of the previous method of gamma irradiation,” says Prof Anna. Additionally, she adds, “An improved understanding of rice genomes and marker-assisted technologies have also enabled researchers to conduct more targeted breeding efforts, as well as enabled the selection of new rice varieties for desired traits at the molecular level”.

As the research has advanced, the work that Prof Anna and the team of researchers have accomplished has gained significant recognition. One of their biggest breakthroughs, the rice variety NMR152 produced through collaborative efforts with the Malaysia Nuclear Agency and other institutions, has received the “Certification of Registration of New Plant Variety and Grant of Breeder’s Right” by the Department of Agriculture, Malaysia.

On top of that, the research team has also received international recognition for their work. In 2017 and again in 2020, the team was awarded the FNCA Excellent Research Team by Forum for Nuclear Cooperation in Asia (FNCA). In 2021, they were given the Outstanding Achievement Award in Plant Mutation Breeding by the International Atomic Agency (IAEA) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

A Thriving Ecosystem

The research into new rice varieties is not just about developing new rice strains. Research has driven innovation in the agriculture sectors by enhancing food productivity and sustainability through the development of new technologies, practices and techniques.

For example, Prof Anna explains that the research has generated valuable data on the performance of different rice varieties under varying environmental conditions. By combining this data with advanced analytics and modelling techniques, farmers can make informed decisions about crop management practices, input use and variety selection to maximise productivity and profitability. “This is called data-driven decision making,” explains Prof Anna.

There has also been a rise in precision agriculture where research and innovation have reduced the burden of farmers by using technology to enhance proper field management. Precision agriculture uses technological advancements such as remote sensing, drones, robotics and GPS-guided machinery, to optimise resource use and improve productivity in rice cultivation. “Research into new rice strains complements these technologies by providing varieties that are well-suited to precision agriculture practices, resulting in higher yields and reduced input costs,” Prof Anna adds.

Challenging Environments

Some of the biggest challenges facing the research are the lack of funding and the lack of more advanced equipment. Prof Anna also says that there is a need for producing more local experts in the biotechnology field. Her own involvement in the research was sparked by a personal passion to contribute to the country’s sustainable food resource. “Generally, this study is also in line with the national food security policy 2021 – 2025. As the SSR decreased, by conducting this research, IMU was able to contribute to the increase in the income of farmers in particular and contribute to the increase in the national SSR in general,” she says.

However, she also hopes that her connections and network with research like this will enable her students to become more proficient in areas related to the food and agriculture sectors. “We need more scientists,” she says, adding, “and I hope that we can provide not just the skills, knowledge and opportunities but also the inspiration and motivation for our future researchers.”