If you ask me what the most important language in the world is, I would reply without hesitation: Mathematics. Mathematics governs almost every single aspect of our daily lives. In medicine, it manifests itself as evidence-based medicine (EBM).

After learning about statistical theory during ‘A’ levels, I was especially thrilled to be able to apply it to the real world finally. Its power over clinical practice intrigued me – barring exceptional circumstances, our guidelines are dictated by practices which have been shown to fulfil a very simple equation, p ≤ 0.05.

I thus read with interest an email invitation to join a Cochrane Malaysia blog-writing competition organised in conjunction with Students4BestEvidence (S4BE), an award-winning UK-based blog. 2 topics were given: (1) evidence-based practice – a fairytale or reality; and (2) challenges in evidence-based medicine and how I overcame them.  I found the former fascinating. IMU’s strong emphasis on EBM meant that we had EBM embedded in our syllabus ever since our Semester 1 community medicine module. This was followed up with a small, heavily-supervised mini-research project in Semester 5, and then a major one over the course of Year 4. Even in our portfolio of 10 case write-ups required for our exit viva, we were required to incorporate the usage of EBM in each write-up to examine if the management of our patients was indeed the best practice supported by current literature. If evidence-based practice were indeed a fairytale, could this all be for naught? I thus saw this competition as an opportunity to explore evidence-based medicine in detail. Reading further into the history of EBM and its statistical interpretation, I was surprised to discover that our understanding of the p-value is flawed. At its crux, while we take the p-value to be a statement on the truth of our null hypothesis, it is in actuality a reflection of how compatible the research data is with the hypothesis. Compatibility does not necessarily equate to truth. Furthermore, the threshold of statistical significance 0.05 is an arbitrary value set by Fisher, the pioneer of modern statistical science. This then raises the question – why 0.05 rather than 0.01 or 0.1?

I found the former fascinating. IMU’s strong emphasis on EBM meant that we had EBM embedded in our syllabus ever since our Semester 1 community medicine module. This was followed up with a small, heavily-supervised mini-research project in Semester 5, and then a major one over the course of Year 4. Even in our portfolio of 10 case write-ups required for our exit viva, we were required to incorporate the usage of EBM in each write-up to examine if the management of our patients was indeed the best practice supported by current literature. If evidence-based practice were indeed a fairytale, could this all be for naught? I thus saw this competition as an opportunity to explore evidence-based medicine in detail. Reading further into the history of EBM and its statistical interpretation, I was surprised to discover that our understanding of the p-value is flawed. At its crux, while we take the p-value to be a statement on the truth of our null hypothesis, it is in actuality a reflection of how compatible the research data is with the hypothesis. Compatibility does not necessarily equate to truth. Furthermore, the threshold of statistical significance 0.05 is an arbitrary value set by Fisher, the pioneer of modern statistical science. This then raises the question – why 0.05 rather than 0.01 or 0.1?

The more I read, the more issues I found with EBM. I explored the key ones in my essay submission to the Cochrane Malaysia contest, which then went on to clinch the 1st prize. Despite my essay painting a bleak picture of EBM, it must be stressed that it is important to not write it off as an exercise in futility, as evidence-based practice has ushered in huge reforms in the way we practice medicine, benefiting countless of patients. We nevertheless should keep those issues in mind and continue refining our understanding of the mathematics behind EBM, so as to better the healthcare we afford our patients.

Placing first in the contest was a welcome bonus to the knowledge gained during the writing process, both of which made my week-long sleep deprivation worth it. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dr Ng Kian Seng for reviewing my essay prior to submission, and also congratulate my colleagues from School of Pharmacy (Chin Yuh Haur, Lee Chen Yuan, and Lee Kar Yen) for winning the 3rd prize!

Written by: Goh Zhong Ning Leonard, IMU‘s Medical Student from ME1/13 cohort.

Leonard’s entry can be found at Evidence-based health practice: a fairytale or reality?

Congratulations to Leonard, Chin Yuh Haur, Lee Chen Yuan, and Lee Kar Yen!

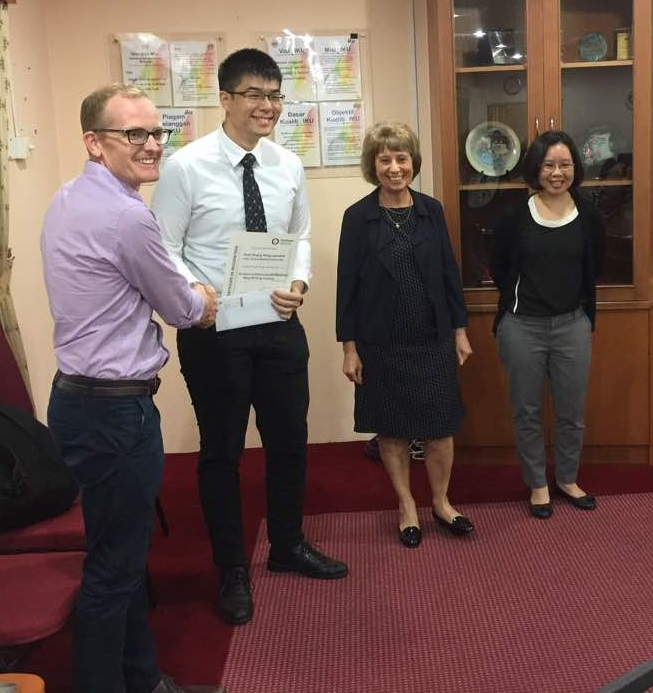

The prizes were presented by Steve McDonald Co-Director of Cochrane Australia on 4 December, 2017 at a small ceremony in the Dahlia meeting room at the Public Health Institute, KL in the presence of the Malaysian Cochrane Coordinating Group, Prof Mallikarjuna Rao Pichika, Associate Dean for Research & Consultancy, School of Pharmacy, IMU and A/Prof Hally Sreerama Reddy Chandrashekhar Thummala, Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine IMU.

The prizes were presented by Steve McDonald Co-Director of Cochrane Australia on 4 December, 2017 at a small ceremony in the Dahlia meeting room at the Public Health Institute, KL in the presence of the Malaysian Cochrane Coordinating Group, Prof Mallikarjuna Rao Pichika, Associate Dean for Research & Consultancy, School of Pharmacy, IMU and A/Prof Hally Sreerama Reddy Chandrashekhar Thummala, Department of Community Medicine, School of Medicine IMU.

No approved comments.